*pictured Gracie Barra training vs ADCC 2013 training camp

A provocative video from black belt Sam Gaier posed an interesting question. According to Gaier, the persistent emphasis on gi training at many academies might have less to do with technical development and more to do with business strategy.

“Your coach isn’t having you train in the gi because it’s making you more technical,” Gaier states bluntly in the clip. “He’s having you train in the gi because that’s his moneymaker at the gym.”

The claim strikes at something many practitioners may have suspected but rarely voiced openly. Gaier recounts conversations with other instructors when he opened his own facility.

“Coaches explained this to me like they were giving me some secret,” he says. “They’re like, it’ll attract the demographic of people who can afford jujitsu, which is 35 to 45, a lot more than no gi will.”

This demographic targeting drives scheduling decisions that prioritize gi classes regardless of which format might better serve students’ competitive or technical goals.

“That is why they’re telling you to train in the gi because they want most of their practices to be the gi because that’s what makes them money,” he explains.

The revenue model becomes clearer when considering equipment requirements. A quality gi can range from $100 to $400 with some academies requiring gym-branded uniforms and additional patches. Students typically purchase multiple gis to rotate between training sessions. No-gi training, by contrast, requires only affordable athletic wear most people already own.

The money incentive is even bigger for huge affiliations. Gracie Barra notably struck a deal with adidas some years back to sell their gis to all their members.

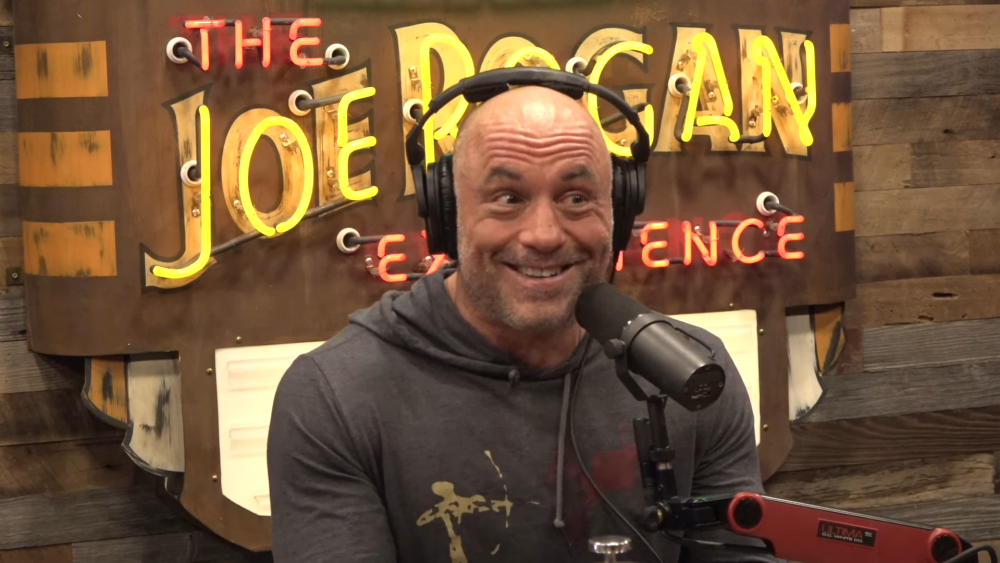

Gaier’s perspective finds unexpected alignment with comments from elite competitors who have publicly favored no-gi training for different stated reasons. Gordon Ryan told Joe Rogan that his preference comes down to simple enjoyment.

“But the thing about the Gi is, it’s just not as fun for me to train in the Gi as it is to train Nogi,” Ryan explained. “I find it’s much more enjoyable for me to train Nogi than it is in the Gi. So I feel like if I don’t enjoy doing it, why am I going to do it in the first place?”

Ryan’s reasoning extends to his competitive legacy.

“Like I’m already so good Nogi, I feel like I’m, you know, the best in the world, basically the best ever,” he stated. “Why would I take time away from that legacy to pursue something that I’m not even really particularly interested in?”

Beyond personal preference, Ryan offers a market prediction that supports Gaier’s business analysis.

“And honestly, that’s dying in America. Like in the next 10 years, the Gi is pretty much going to be phased out as far as competitions in America,” Ryan said. “It’s going to be like a novelty where they have like some competitions here and there, but Nogi, as far as numbers support, Nogi is the way of the future.”

But this doesn’t mean the technical comments are off base. Keenan Cornelius characterized no-gi as simpler in its conceptual demands.

“Even though no-gi is a simplified version of gi for people with less brain power, I appreciate the simplicity,” Cornelius said.

He elaborated on the mental approach required.

“It’s so simple. You actually have to underthink. You need to think less energy than you have to think in the gi. And that can be liberating,” Cornelius explained. “If you move the checker piece harder and faster and with more steroids, you have a higher chance of winning.”

Cornelius later removed these comments from his social media after they generated significant controversy within the community.

Gaier emphasizes that his criticism targets deception rather than business itself.

“I’m not faulting them for wanting to run a successful business,” he clarifies. “I will fault them for lying to you and telling you that the gi is making you more technical because they know that it’s not that.”

Community responses have been predictably mixed. Some practitioners defended gi training’s complexity and the additional strategic options it provides through grip fighting and cloth-based control systems. Others acknowledged the economic pressures facing academy owners who need reliable revenue streams to maintain facilities.

One recurring theme in the discussion centers on mandatory uniform policies. Some academies require students to purchase gym-branded gis sometimes at premium prices as a condition of membership. These requirements transform what might be a one-time equipment purchase into an ongoing revenue source through branded merchandise.

The generational component of the debate also surfaces repeatedly. Several commenters noted that gi training allows older practitioners to remain competitive longer as the slower pace and additional grip options can offset declining athleticism. This reality may genuinely serve the needs of the 35-45 demographic Gaier mentions even as it aligns with business interests.

Whether gi training truly develops more technical proficiency than no-gi remains an open question. In the end of the day most martial arts including jiu-jitsu are invididual sports. Realistically this means there’s a big discrepancy in skill even between teammates at different academies.